“Biological Manufacturing” is an area that uses “living cells as micro-factories”. The idea behind biological manufacturing is similar to making “beer,” but it’s produced at a high-tech, life-saving level rather than a low-cost, mass-produced level. Biological manufacturing uses “micro-factories” (ranging from simple bacteria to specialized hamster cells) to produce medicines, antibodies, and vaccines through a combination of chemistry and biology. This is the foundation of modern medicine and has enabled treatments once considered science fiction.

However, achieving successful results in biological manufacturing is where the true challenges begin. In the context of biologics manufacturing, you cannot simply take a biological “blueprint” and multiply it by a million like you could if you were producing auto parts. Biologics manufacturing is more like baking a perfectly formed cupcake than creating a flawless cake the size of a swimming pool. These “chefs,” or living cells, become stressed in large metal vats, resulting in “bad” batches of product that cost millions and delay patients from receiving necessary therapy.

Scientists and engineers are overcoming barriers to large-scale production by developing new manufacturing approaches. These innovations include such developments as using artificial intelligence (AI) to forecast the ideal growing conditions for products and/or develop “assembly line” type of continuous manufacturing processes that enable the movement of products from lab discovery to commercialization to assist many people.

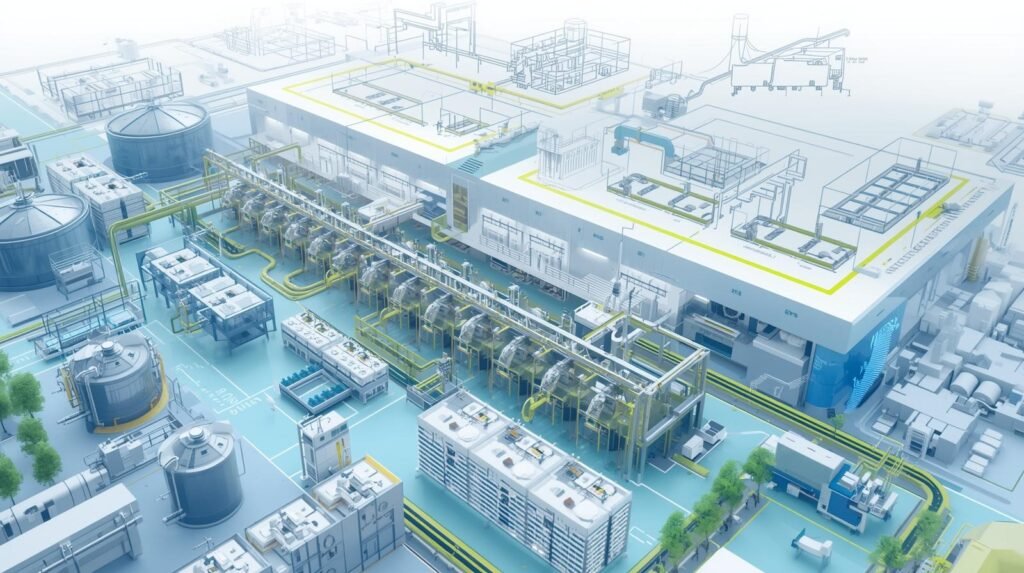

One of the biggest challenges in developing biologics, enzymes, and other cell-based products is translating lab-scale processes into commercially viable manufacturing systems. Scaling strategies for biomanufacturing must address all three primary drivers of goods cost: product quality, increased production volume, and reduced regulatory burden.

Begin by understanding the most critical variables affecting performance. Using risk assessment approaches will help identify which “scale-sensitive” variables are present in the bioprocess (e.g., mixing, gas transfer, shear forces, thermal management, hold times). The best scaling strategies for biomanufacturing will be based upon validated laboratory models that approximate the larger tank sizes being developed; therefore, a significant advantage is gained by testing design changes in a timely manner with minimal economic exposure.

Scale up for robustness, not maximum yield. Develop and document a proven operating window for key variables, including pH, temperature, feeding schedules, and agitation speed. Incorporate in-process control and/or real-time monitoring wherever practical. Scaling strategies for biomanufacturing methods that promote product uniformity across batches will facilitate technology transfer across locations and/or with different partner companies.

Scale-up planning is most effective when both upstream and downstream processes are planned in tandem. If the titer of an upstream process is too high, it may exceed the capacity of the downstream processes (i.e., filtration, chromatography, etc.), or potentially overload the preparation of buffers necessary for downstream processing. Therefore, consider opportunities for debottlenecking from the outset of scale-up planning, using techniques such as single-use flowpaths, intensified/continuous processing strategies, optimized column sizing, and/or improved scheduling of shared utility systems.

Scaling strategies for biomanufacturing that treat the manufacturing facility as a single integrated system (rather than individual unit operations) will yield strong results. Digital tools also offer a significant opportunity to accelerate learning and implementation through advanced analytics that link process parameters to CQAs and through automation that reduces the potential for human error. Several companies have adopted Process Analytical Technology (PAT), Electronic Batch Records (EBRs), and Model-Based Control (MBC).

The application of these technologies and associated scaling strategies for biomanufacturing will significantly improve the ability to prevent deviations and expedite investigations when they occur.

Finally, the scaling strategies for biomanufacturing should include plans for your supply chain and workforce. Ensure that you have secured all required raw materials, qualified alternate suppliers, provided standardized training to all employees on all shifts, and documented your decision-making processes and validation logic as you execute the scale-up activities. Scaling strategies for Biomanufacturing that effectively integrate science, engineering, quality, and operations will enable the reliable growth of biomanufacturing processes with each subsequent batch.

Why Making More Isn’t as Simple as Multiplying the Recipe

Anybody who has ever cooked will tell you that you cannot simply take a cake recipe and multiply all of the ingredients by one hundred and expect to have a perfect result. You may find that the center does not cook, and the edges are burnt; this is essentially the same problem that exists in the biomanufacturing industry. However, whereas a cake-burning incident can be costly and potentially disastrous, failure at an industrial scale can be far more costly and potentially disastrous.

The problem lies within the recipe itself. The conditions necessary to keep cells happy and producing product in a small lab dish do not necessarily translate well to an industrial environment.

To overcome this problem, manufacturers use a bioreactor. A bioreactor is a large, highly controlled, sterile container that provides optimal conditions for cell growth. Bioreactors come in many different sizes (from a few liters to the size of a small school bus) and are used to control the temperature, pH, and nutrient levels within the vessel. They are much more than a large mixing bowl; they function as a high-tech life support system for billions of tiny living factories.

While controlling the conditions within a bioreactor is important, ensuring each individual cell receives adequate oxygen within the vessel is difficult. If the mixture inside the bioreactor is not properly agitated, cold spots can develop where some areas of the bioreactor contain inadequate oxygen levels, and waste products can accumulate in certain areas of the bioreactor and become toxic to the cells creating those waste products. The formation of cold spots and the accumulation of toxic waste products are significant challenges to scaling up bioprocessing operations.

Collectively, these problems create cellular stress. Cellular stress occurs when cells receive either too little oxygen, too little food, or toxins. When cells experience cellular stress, they stop producing product (i.e., the valuable medication or protein) and/or may die, resulting in the loss of a potential multi-million-dollar batch. As such, the choice of cell culture container is one of the most critical decisions in developing a viable manufacturing process.

Biomanufacturing Processes – Core Upstream and Downstream Workflows Supporting Large-Scale Production

Biomanufacturing for large-scale biologics production requires the same level of discipline as other large-scale manufacturing processes, but with additional challenges of integrating upstream cell culture and downstream purification while maintaining quality and regulatory compliance. Biomanufacturing processes are intended to be repeatable, measurable, and resistant to variability, because even minor changes can affect yield, purity, and the product’s critical quality attributes. The importance of scaling strategies for biomanufacturing becomes apparent when we consider that as volumes, equipment, and throughputs increase, performance should remain consistent.

In the upstream phase, most biomanufacturing processes begin with cell line development and banking. Subsequently, the process expands the seed train to produce a viable and consistent inoculum. As production increases to larger bioreactors, teams need to control mixing, oxygen transfer, CO2 removal, and shear to preserve cell viability and productivity. Successful scaling strategies for biomanufacturing typically involve using small-scale models and process characterization studies to determine how each of the above parameters behaves at larger scales.

The typical downstream process will include harvest and clarification (e.g., centrifugation and/or depth filtration), followed by capture chromatography, polishing steps, and viral clearance. Ultrafiltration/Diafiltration is used to concentrate the product and perform buffer exchange prior to formulation. Biomanufacturing processes must balance downstream steps against upstream outputs. The higher the titer, the greater the potential bottleneck in filtration capacity, resin lifetime, and buffer logistics. Practical methods for scaling biomanufacturing processes include debottlenecking with appropriately sized columns, optimizing cycle scheduling, and using single-use flow paths when appropriate.

In addition to biomanufacturing processes in both areas, analytical and quality systems are integral to biomanufacturing. Analytical tools, such as in-process testing, PAT when feasible, and trending deviation data, help detect early drift. Automation, electronic batch records, and standardization of sampling practices help reduce human error and expedite investigations. When scaling a facility, the same principles used to develop scaling strategies for biomanufacturing apply to raw material qualification, supplier redundancy, and workforce training to ensure consistent process execution.

When designing and executing biomanufacturing processes as an integrated whole, scaling is reduced from an art based on trial and error to a science-based, controlled, data-driven method for expanding production while protecting quality.

Biomanufacturing Methods – Proven Techniques for Reliable and Efficient Biomanufacturing Scale-Up

Reliable scale-up relies heavily on identifying biomanufacturing methods that ensure product quality as throughput increases and costs decrease. Therefore, the most successful Biomanufacturing Methods are those that have been validated during development, are transferable to different locations, and have defined control strategies. As a result, it is beneficial to develop your scaling strategies for biomanufacturing alongside your initial method selection, rather than adding them after problems arise.

Biomanufacturing Methods for Upstream Production will typically include robust cell banking, consistent seed train expansion, and well-defined media and feed programs as foundational methods. During scale-up, these processes typically use geometric and process-based criteria (e.g., power input, tip speed, or oxygen transfer rate) to maintain consistent growth and productivity rates.

Another practical approach to scaling strategies for biomanufacturing is to use scale-down models that replicate large-reactor conditions, allowing engineers to rapidly evaluate the effects of agitator speed, aeration, and feeding on the process without risking a full-scale batch loss. In addition to scale-down modeling, biomanufacturing methods focused on monitoring include online sensing systems, PAT when feasible, and tight control of pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen levels to minimize variability.

Common downstream Biomanufacturing Methods for clarification aim to simplify purification while maximizing recovery. When selecting an appropriate clarification method (e.g., centrifugation, depth filtration), consider the expected solids concentration and volume.

While chromatography remains central to purification, key strategies for successful scaling in Biomanufacturing Methods that reduce cycle time and variability include optimal residence time, standardization of column packing (pre-packed columns), and life-cycle management of resin performance. Early planning for capacity will also help ensure that increases in upstream titer do not overburden filtration, buffer preparation, or column use.

Process intensification and modular design are increasingly important Biomanufacturing Methods for scaling. Single-use technologies can reduce changeover burden and cleaning requirements, whereas hybrid facilities combine disposable flow paths with stainless-steel assets to provide cost flexibility.

Also, Continuous or semi-Continuous operations (perfusion upstream, Continuous chromatography downstream) are Biomanufacturing Methods that can increase output without simply building larger tanks. However, these approaches require careful control of each operation and a strong data system; they align well with modern scaling strategies for biomanufacturing.

Standardization is a method itself. Documented procedures, operator training, electronic batch records, and deviation trending are Biomanufacturing Methods that will make performance repeatable across shifts and sites. Organizations using this approach, along with clear scaling strategies for biomanufacturing, will find scale-up more predictable, efficient, and compliant from pilot to commercial manufacturing.

Advanced Biomanufacturing – Next-Generation Technologies Enabling Scalable Biomanufacturing Operations

Advanced Biomanufacturing is changing how biologics and other bio-based products move from R&D to full-scale manufacturing. By leveraging automation, flexible platforms, and big data, Advanced Biomanufacturing will be able to produce greater amounts of product while maintaining product quality. The majority of teams are simply looking for a few things: a way to scale up faster and more predictably, and at lower cost. To accomplish this, Advanced Biomanufacturing will need clear and effective scaling strategies.

A key driver for Advanced Biomanufacturing is Process Intensification (PI). Upstream perfusion and high-cell-density cultures enable greater productivity in smaller footprints, thereby eliminating the need for very large bioreactors. PI also requires close monitoring and control; therefore, Advanced Biomanufacturing typically includes advanced sensors, automated feeding systems, and model-based control loops. When executed effectively, Advanced Biomanufacturing will enhance scaling strategies by reducing variability and enabling a smoother transition across scales and sites.

On the Downstream side, Advanced Biomanufacturing is also advancing rapidly with continuous and semi-continuous purification options. Multi-column chromatography, inline dilution, and closed single-use fluid handling can help reduce hold times, lower the risk of contamination, and increase throughput. Because downstream is likely to be the limiting factor as upstream titer increases, Advanced Biomanufacturing will support scaling strategies for biomanufacturing by increasing cycle efficiency, enhancing capacity planning, and reducing changeover time.

Advanced Biomanufacturing represents a second pillar of Digitalization. Real-time data capture, along with advanced analytics, enables teams to track product-quality process parameters and rapidly detect operational changes. A number of organizations combine Advanced Biomanufacturing with Process Analytical Technology (PAT) (such as electronic batch records and automated deviation workflow systems).

All these technologies support scaling strategies for biomanufacturing by reducing investigation time, enabling more rigorous comparisons during technology transfer, and increasing learning cycle time.

Facility design is also changing. Advanced Biomanufacturing has shifted from using traditional fixed-facility designs to using modular, hybrid, or single-use facility designs. This allows the same space to be used to manufacture multiple products.

Reduced capital expenditures are achieved through this flexible facility design, which enables multi-product manufacturing. Essentially, Advanced Biomanufacturing enables the addition of “manufacturing modules” to produce additional products while maintaining operations at an existing plant; this approach is well aligned with current scaling strategies for biomanufacturing.

In summary, Advanced Biomanufacturing utilizes intensified processing, continuous processing, automation, and digital controls to make the process of scaling less dependent on trial and error and more dependent upon consistent and repeatable performance — providing scaling strategies for biomanufacturing that will deliver results faster, be more resilient, and will be capable of meeting the needs of future generation product pipelines.

The Ultimate Choice: A Reusable Steel Kitchen vs. A High-Tech Disposable Bag

While the decision about how large to build your bioreactor is an important first step in the manufacturing process for a bio/pharmaceutical company, there is a second very important decision that may seem like it’s an easy one – do you build a steel tank that will last many years and can be cleaned and reused, or do you use a sterile plastic bag?

The industry had traditionally been built using big, shiny, stainless steel bioreactors – think of them as the huge pots in a commercial kitchen – they’re long-lasting, reliable, and have been used for years. In recent years, a newer, more agile technology has emerged and completely transformed the industry: single-use bioreactors (also called single-use bags). These are large, advanced, pre-sterile plastic bags placed inside a support frame.

What single-use technology has enabled is the elimination of tank cleaning. When you finish a batch in a stainless steel tank, you must complete a sterilization process that can take several days to several weeks to prepare the equipment for reuse. There is also a significant risk of contamination when cleaning and sterilization are not performed properly.

The risk of cross-contamination (when small amounts of a previous product contaminate the next) is extremely high if the cleaning and sterilizing aren’t done correctly. A major advantage of single-use technology is that it eliminates these issues by removing the used bag and replacing it with a new one. This allows a facility to produce a vaccine and immediately begin producing a cancer therapy, with no risk of contamination or carryover.

Will the bag always be optimal? No, because this decision will be based on the goals of your mission. Companies must consider both the advantages (e.g., volume) and disadvantages (e.g., flexibility) of the two options listed above.

- Stainless Steel: Best for producing large amounts of a single, “block buster” drug (like insulin) in a continuous fashion.

- Single Use: Best for companies with multiple products, which are produced in small batches; for companies that need to get their products into clinical trials as soon as possible.

The type of container you use will ultimately determine how the “cooking” process is performed. In addition to eliminating the time-consuming cleaning required for stainless steel bags, single-use technology enables significantly faster, more efficient production.

Moving Past the ‘Bake and Wait’ Model: The Power of Continuous Production

Traditionally, producing biotherapeutics has been much like baking: a large tank (bioreactor) containing all the necessary ingredients (cells, broth) would be filled and incubated for several weeks. This traditional method of producing a large quantity of product at once in a single tank (batch production), is an all-or-nothing risk; either the batch will contain the desired product or the batch will have failed due to some event, such as contamination or a slight temperature fluctuation, resulting in the loss of the entire batch, costing millions of dollars.

The current batch production model for manufacturing biotherapeutic products is being replaced by continuous biomanufacturing. The concept of this method is to maintain a continuous flow of product through the manufacturing process, rather than producing in batches. Instead of filling a tank with all of the required ingredients (raw materials) and allowing the tank to incubate for several weeks, a small continuous stream of raw materials will enter the bioreactor, where the cells will continue to produce the drug continuously, and a purified product will exit the bioreactor on a continuous basis.

The shift to this type of manufacturing requires developing a robust, continuous biologics manufacturing process rather than a series of discrete steps.

Many of the benefits of the new model could be substantial. First, because the equipment will be much smaller and run continuously, facilities will be able to produce the same quantity of medication in significantly less space than before. Second, and more importantly, it substantially reduces risk. In a continuous process, if something goes wrong, it may spoil only a couple of hours of production instead of a month’s worth. Lastly, continuous production of the drug substance greatly improves and simplifies the final major purification step, which is the primary bottleneck in Downstream Processing.

Of course, overseeing the continuous operation of microscale manufacturing processes that cannot be stopped requires extensive monitoring. You can no longer simply test a sample of the product when the process is complete. You must monitor both the overall health and the productivity of these ‘living’ factories in “real time” while the process is occurring. However, how do you monitor one trillion individual cells that are inside a vessel without opening the vessel or door?

How Do You Check on a Trillion Cells? With Smart Sensors and Real-Time Data

The key to creating a successful cell-culture product lies in Process Analytical Technology (PAT), which uses advanced internal bioreactor sensors to measure cell performance in real time. Think of it like a personal trainer or doctor that lives inside the bioreactor with an advanced “fitness tracker” sensor that measures the temperature of the culture and an “inventory tracker” sensor that monitors the concentration of nutrients available and waste products produced; both send data back to the team in charge of the bioreactor in real-time so they know exactly when to intervene to keep the process perfect.

In contrast to the old “bake and wait” method of production, in which problems went undetected until they were discovered through sampling and testing after the fact, a team using PAT will immediately detect that their cells are experiencing stress due to nutrient depletion, among other factors. It’s much like your car’s dashboard warning light when you are low on oil, versus a repairman telling you why your car died after the fact. Through this real-time feedback mechanism, the process can remain on course.

This rapid response capability based on proactive management of a bioprocess is a component of a broader manufacturing philosophy referred to as Quality by Design (QbD), which holds the view that quality should be designed into each step of the manufacturing process from the very start rather than simply being checked for at the end of the process. Rather than hope for a good result, you design a system in such a way that undesirable results are essentially impossible.

While PAT provides the necessary vision and hearing for QbD, would it not be nice to have not only the ability to perceive the current state of your cells, but to be able to forecast their future behavior?

Building a ‘Flight Simulator’ for a Bioreactor: How AI Predicts the Future

The constant data streams from smart sensors are more than merely health records; they are the fuel for artificial intelligence (AI). Using a continuous stream of live data, researchers develop a digital twin—a fully virtual replica of the bioreactor. Think of it like an ultra-realistic flight simulator for the manufacturing process. That digital representation of the bioreactor enables the researcher to test thousands of “what ifs” and simulate system crashes without loss of materials or living cells.

The researchers develop very small, precisely replicated miniature bioreactors in the laboratory to make the simulator highly accurate. The researchers use scale-down modeling—similar to developing a mini-test kitchen — to test recipe ingredients before making the large batch. The researchers use a controlled, very small-scale environment to safely push the cells to their limits and determine how they respond. The data generated by the researchers is critical to the AI learning how the real-world, full-scale system will behave in response to every possible situation—good or bad.

Using this strong combination, the AI is a predictive force to be reckoned with. The AI can evaluate numerous variables to identify the optimal “recipe” that maximizes performance and acts as a prognosticator, identifying early signs of potential problems well before they arise in the real world. This virtual crystal ball not only prevents costly errors but also maximizes the probability of success for every batch. However, what occurs when the “batch” is not for millions of people, but is developed specifically for just one?

Biomanufacturing Efficiency – Improving Yield, Speed, and Cost-Effectiveness at Scale

Biomanufacturing efficiency is the ability to produce products at high yields while maintaining a low overall cost and as short a cycle time as possible. In large-scale biomanufacturing, efficiency is determined by numerous small, independent decisions made across the upstream, downstream, analytical, and operational phases of the process. Therefore, strong scaling strategies for biomanufacturing provide a framework for relating those decisions; thus, when improvements are made in one phase of the process, they do not create a bottleneck in another phase.

In the upstream portion of biomanufacturing processes, efficiency improvements typically begin with a stable cell line, a consistent seed train, and optimal media and feed conditions. Control over key parameters such as dissolved oxygen levels, pH, temperature, and feeding conditions will help minimize cellular stress during the manufacturing process and thereby improve productivity.

In many cases, biomanufacturing efficiency has improved by using scale-down models to rapidly test upstream process changes and define “proven acceptable ranges” for each parameter, thereby ensuring a robust process. Both methods are central to developing successful scaling strategies for biomanufacturing, as they have led to fewer failed batches and simplified technology transfer from development to manufacturing.

For the downstream portion of the biomanufacturing process, efficiency depends on both the volume of product produced per unit time and the percentage of product recovered. The sizing of clarification, filtration, and chromatographic equipment must be based on the expected product volumes and titers, along with reasonable expectations regarding the time required to complete each step and the potential lifetime of the resins used.

Additionally, optimizing buffer use and reducing product hold times can increase biomanufacturing efficiency without requiring changes to the fundamental purification train. Scaling strategies for biomanufacturing downstream processes include early identification of potential bottlenecks, intelligent scheduling, and selection of formats (single-use or stainless steel) that align with the organization’s specific product portfolio and changeover requirements.

Data and automation are both large-scale multipliers of Biomanufacturing. Teams using real-time monitoring, electronic batch records, and trend analysis based on alert signals will have higher Biomanufacturing Efficiency than those that do not. The analytics, which link process parameters to the critical quality attribute(s) (CQA), will help identify the most important changes. Tools that support scaling strategies for biomanufacturing will enhance process understanding, improve comparability, and reduce investigation time.

Equally important to tools is operational discipline. Implementing standard work, providing proper training, and ensuring clarity in all material flows will improve Biomanufacturing Efficiency by reducing human error and rework time. Protecting Biomanufacturing Efficiency through supply chain planning—raw material qualification, alternative sourcing, and inventory strategy—will help ensure that downtime from shortages or delayed quality release is avoided.

Biomanufacturing Efficiency at scale is ultimately the result of balancing science, equipment, people, and data. Organizations that treat efficiency as an overall systems goal and consistently apply their own scaling strategies for biomanufacturing will achieve higher yields, faster production, and lower costs while maintaining product quality.

Sustainable Biomanufacturing – Eco-Friendly Approaches for Long-Term Biomanufacturing Growth

Sustainable Biomanufacturing is defined as the development of products and processes that minimize environmental impacts while maintaining product quality, ensuring a reliable supply, and adhering to sound business practices. Sustainable Biomanufacturing at the commercial scale is not a single project; it is a set of design and operational choices made throughout the manufacturing process to reduce total lifecycle energy use, water consumption, waste generation, and emissions.

The most effective Sustainable Biomanufacturing programs link their sustainability objectives to the company’s scaling strategy for biomanufacturing, thereby preventing growth from always resulting in an increased footprint.

Facilities and manufacturing processes are key to the development of Sustainable Biomanufacturing. In addition to improved heat transfer, HVAC, and cleanroom classification, energy-efficient utilities can provide significant reductions in power requirements. Additionally, water-reduction initiatives, such as improved CIP (clean-in-place) optimization, water reuse where feasible, and smart scheduling, will both promote Sustainable Biomanufacturing while reducing operating expenses.

All of these areas will enable scaling strategies for biomanufacturing through facilitating expansion of the operations within the constraints of site utilities..

Sustainable Biomanufacturing is further supported by materials and consumables that contribute to sustainability. This can be achieved through buffer strategies that use higher concentrations at smaller volumes, reduce single-use plastics where possible, and incorporate supplier requirements for lower carbon content across all materials purchased.

Single-use systems in sustainable biomanufacturing can also enhance sustainability by reducing the use of cleaning agents, water consumption, and downtime, particularly in multi-product manufacturing environments. It is necessary to evaluate which strategy is most effective for achieving sustainability from a life-cycle perspective and to integrate this into scaling strategies for biomanufacturing from the earliest stages of development.

Process performance is also a key driver of sustainability. Achieving higher yields with fewer batch failures reduces media and consumable waste and ultimately lowers energy consumption per gram of product. Digital monitoring, automation, and improved process control are strategies to minimize deviations and rework, enhance the sustainability of Sustainable Biomanufacturing, and increase the facility’s operational resilience. As such, these strategies offer practical ways to scale biomanufacturing operations without degrading product quality.

Lastly, waste reduction and circularity must also be included in the overall picture of Sustainable Biomanufacturing. Sustainable Biomanufacturing encompasses establishing segregation and recycling programs, optimizing solvent and chemical use, and partnering with other entities to recover or responsibly dispose of materials. In addition, teams may develop alternative packaging and logistics solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with transporting materials and products.

By measuring the initial impact of an organization’s production processes and establishing specific goals, Sustainable Biomanufacturing can become a continuous improvement program rather than a one-time initiative.

Ultimately, Sustainable Biomanufacturing supports long-term growth by reducing resource requirements and mitigating risks associated with fluctuating energy prices, limited water availability, and changing regulatory requirements. By implementing scaling strategies for biomanufacturing aligned with Sustainable Biomanufacturing principles, companies can expand capacity to produce bioproducts while continually reducing their environmental footprint—without sacrificing quality or supply.

The New Frontier: Scaling for Personalized Cures Like Cell and Gene Therapy

The last question — about how to produce a batch of medicine for an individual — is the root of the most innovative types of treatment today, such as cell and gene therapy. Many of these therapies use patients’ own living cells to produce the “medication,” thereby creating a treatment that is unique to each patient. Therefore, this reverses the traditional bioprocessing challenge (i.e., scaling up a single recipe in a large bioreactor) and necessitates “scale out,” i.e., safely and precisely producing many individualized batches of product side by side in parallel.

It is the difference between baking one cake the size of a car versus operating a bakery that produces 100 different custom birthday cakes.

Only by combining all of the advances described above can we begin to envision the complexities involved in developing a biomanufacturing process for personalized medicines. The single-use bioreactors will handle small product batches (less than 10 liters) without the risk of contamination from previous runs. Furthermore, the “digital twin” technology will serve as a command center for monitoring all individualized patient batches produced in real time. Ultimately, this new paradigm will provide a high degree of confidence in the ability to produce high-quality biologic products for each individualized patient treatment, which would be impossible for humans to accomplish alone.

In summary, these new scaling strategies for biomanufacturing are providing the basis for the creation of a new type of factory — one that is not optimized for the manufacture of a single blockbuster medication, but instead is capable of being used as a flexible manufacturing platform to produce cures that have been individually developed for each patient. The same technologies that enable us to develop vaccines for the masses are also the tools needed to unlock the future of personalized treatments. By transforming a once-artistic process into a science, biomanufacturing is evolving.

Biomanufacturing Trends – Emerging Innovations Shaping the Future of Biomanufacturing

Biomanufacturing Trends are evolving to make the industry move away from “big batches” and toward a smarter, faster, and more flexible way of producing. Many contemporary biomanufacturing trends focus on shortening product development timelines, enhancing product robustness, and ensuring reliable supply for products with diverse characteristics (complex modalities). Biomanufacturing Trends will also inform capacity planning and scaling strategies by defining requirements for large-scale commercialization.

One of the most significant Biomanufacturing Trends is process intensification. There is increased use of high-cell-density and perfusion processes because they can produce higher yields without expanding their footprint. Process intensification, Biomanufacturing Trends, allows capacity to grow using higher productivity, rather than just building bigger equipment. As another example of a significant Biomanufacturing Trends area, continuous and semi-continuous downstream processing are gaining popularity because they can increase throughput, reduce holding time, and provide smoother transitions between unit operations.

Single-use and hybrid facilities remain among the top Biomanufacturing Trends for multi-product manufacturers. Disposable flow pathways help reduce cleaning requirements, shorten changeover time, and enable faster deployment of new lines. Hybrid designs combine the best of both worlds by providing the flexibility of disposable technology while maintaining the durability associated with stainless steel in high-volume applications. Biomanufacturing trends, such as single-use and hybrid designs, support scaling strategies by enabling modular expansion and reducing downtime during growth.

Biomanufacturing Trends are increasing in frequency throughout the biopharmaceutical industry’s value chain and are related to digitalization. The use of sensors and process analytical technology (PAT) and associated systems, such as data historians, electronic batch records, and other advanced technologies, is used to provide better visibility into processes and enable greater control. Analytics and model-based control also provide a means to correlate process parameters with product quality and to identify trends or “drift” that may indicate issues in a production process.

Thus, the implementation of digitalization technologies and analytics supports scaling strategies for biomanufacturing by providing comparable information across locations, enabling faster root-cause analysis, and reducing the incidence of deviations associated with increased production throughput.

The second set of Biomanufacturing Trends relates to the workforce and operational aspects of biomanufacturing: standardization, automation, and “right-first-time” execution. As the diversity of pipeline products continues to grow and supply chains become increasingly unreliable due to various factors, organizations have developed methods to enhance operational resilience through alternative sourcing options, improved raw material qualification, and risk-based validation. These operational Biomanufacturing Trends support scaling strategies by maintaining reliable supply sources as production volumes increase.

The third set of Biomanufacturing Trends includes sustainability. Sustainability has evolved from being a desirable practice to an expected practice. Examples of sustainability practices include energy optimization, water conservation, and materials lifecycle thinking. As the above Biomanufacturing Trends continue to develop, companies that successfully implement innovative products and processes using disciplined scaling strategies for biomanufacturing will likely experience growth that is faster, more flexible, and more sustainable than those that do not.

From Art to Science: The Future of Biomanufacturing

Advances have made what was once a biological impossibility (scaling up the complexity of biological processes) into a predictable science. An important part of this process has been developing a systematic approach to the translation of a delicate biological “recipe” into a reliable manufacturing process – no longer a “black-box”, but now a problem to be solved through an emerging architecture of innovative engineering.

These advances are driven by novel methods that convert unpredictability into reliability. Flexible, one-time use facilities function as flexible workshops; continuous manufacturing establishes a continuous production line for molecules; smart sensors monitor the living cells continuously; and artificial intelligence provides scientists with a “crystal-ball” type of tool to evaluate possibilities and forecast results. In aggregate, these technologies constitute a powerful set of tools for scaling up the biological world, ensuring that methods successfully used in laboratory environments can also be effectively employed globally.

The future of biomanufacturing extends beyond medicine. The same approaches will be fundamental to sustainable food production without environmental harm, to creating biodegradable plastics, and to producing clean biofuels. A quiet revolution is underway – it seeks to tame the microscopic world to address humanity’s largest macroscopic challenges.