At one point, you have probably watched your robot vacuum move around your house cleaning and thought to yourself, “It seems like it knows exactly where it is.” That is not possible through GPS alone. The answer lies in a complex method of creating a map of an area (the robot) and determining its position relative to that map while the map is being created. The ability to do this is the basis for how robot mapping functions in any indoor space.

To understand why this problem is so difficult to solve, think about a shopping mall. The architects’ primary responsibility is Mapping—the creation of the first-ever mall directory. On the other hand, as a shopper, your primary function is Localization—finding the “You Are Here” pin on the existing map. Since most of us use existing maps to navigate, our experience typically keeps mapping and localization as two completely separate tasks. Autonomous robots will need to perform both tasks concurrently to create a usable map of their environment.

Next, consider a robot entering a building with no directory. In addition to mapping the space, the robot must determine its position within the map. How could a robot possibly locate itself on a map that is still being constructed? The solution to this challenging problem underpins SLAM.

These sophisticated self-localization methods for robots enable them to efficiently navigate environments they have never visited before — whether it is your living room or a cave on Mars.

Summary

This guide explains SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping), the core technology that enables robots to understand their surroundings and build a map of their environment. Robots often operate in areas without GPS, such as warehouses, hospitals, office spaces, and private homes; therefore, they rely on sensors and sophisticated algorithms to estimate their location, identify and avoid obstacles, and generate safe routes.

SLAM explained in plain language: A robot collects observations using cameras, LiDAR, wheel odometry, and Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs). The algorithm fuses sensor data to generate a consistent estimate of both motion and location. While the robot moves, its map is updated in real time. The robot identifies landmarks when they reappear and corrects errors by “loop closing” to previously visited locations in the map.

The guide also explains the difference between 2D and 3D mapping, how map quality affects robot navigation, and how the planning and control processes take a map and convert it into smooth motion.

Finally, the guide addresses the most common issues related to SLAM, including noise, drift, changes in light, reflective surfaces, and changing obstacles, and the methods that can be applied to ensure that robot positioning and location will remain accurate and reliable in real-world environments.

SLAM: robots build a map and pinpoint their location in real time

Many robots use Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), a technique that creates a map of their surroundings and determines their current position simultaneously. A good map is necessary to plan routes safely. Similarly, if the robot does not know its exact position, it cannot properly update the map with the new information. By continuously updating the robot’s estimated position and the map during exploration, SLAM resolves both issues simultaneously.

The robot typically uses a combination of sensors, such as cameras, LiDAR, radar, wheel encoders, and an inertial measurement unit (IMU), to collect data about its surroundings. Data collected by each sensor type is fused using various techniques, giving the robot a better understanding of the world than a single data source could provide. As the robot explores its environment, SLAM estimates the movement of the robot based on feature tracking in the environment (such as corners, edges, or reflective surfaces) and compares what it sees now to what it saw a short time prior to assist in estimating motion, detecting drift, and correcting any errors made.

Once the robot has completed a full exploration of the area, SLAM may generate a 2D floor plan for indoor navigation or a 3D map for aerial or land-based autonomous vehicles. The resulting map may take the form of a grid indicating occupied versus free space, a collection of landmarks representing specific objects or locations, or a point cloud representing all sensor measurements collected during exploration. Since the mapping process occurs in real time, the robot can adapt to new obstacles encountered during operation and dynamically update its internal map representation. Additionally, good SLAM implementations support “loop closure,” the ability to recognize previously visited areas and align the map.

Different algorithms make trade-offs that are based on the algorithm used. Visual SLAM works well in textured spaces because it relies on cameras, but can be affected by low light. Lidar-based systems provide precise distance measurements in darkness and can operate in low-light conditions; however, the sensors used in these systems can be expensive. A common approach is to use both cameras and lidar systems together, adding GPS when available outdoors. In warehouses, hospitals, and homes, robots equipped with SLAM can deliver items, clean floors, and escort people. Simply stated, SLAM is a key component of reliable autonomy.

Even though math can provide strong foundations for SLAM technology, SLAM technology isn’t magic. Fast motion, shiny surfaces, and crowds can introduce confusion in sensor data, and small errors can accumulate over long distances. To mitigate this issue, engineers have developed improved calibration methods, probabilistic filters, and uncertainty-aware optimization methods. Also, engineers design maps that are compact enough to compute on embedded hardware.

As chips continue to get faster and learning-based perception improves, SLAM technology is moving from research laboratories into products that consumers can purchase, enabling robots to move confidently through the world. For users, the result is simple: a robot that can start in a new environment, learn it quickly, and keep navigating even as the environment changes around it daily.

The Real Challenge: Solving the “Lost in the Dark” Problem

When we examined what a robot needs to do to locate itself (the localization problem) and to build a map (the mapping problem), we realized they were interdependent. In other words, before a robot can use its localization system to build a map, it has to know exactly where it is.

That creates a very difficult situation known as a chicken-and-egg problem. Before you can add the leg of a chair to your mental map, you have to know exactly where you are located. And before you can determine exactly where you are located, you need to know the positions of the landmarks on a map that you have not yet created. The simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) problem is arguably the hardest technical problem in robotics.

To solve the SLAM problem, the robot will not attempt to solve it all at once. Instead, the robot will break down the task into many small loops. The robot begins by making an initial educated guess about its current location. Based on that estimate, the robot will move forward slightly, using its sensors to measure distances to nearby objects. When it reaches its new location, it measures the distance to that object again. If the object is not located at the exact distance that the robot had previously guessed it would be, then the robot updates both the object’s position and the robot’s estimated position.

The loop of guessing, measuring, updating, and repeating will continue until the robot has mapped its entire environment. This process enables a new robot vacuum cleaner to navigate your home without a prior map of your living space. However, for the above to occur, the robot must first perceive the environment in a way that allows it to see the landmarks. How the robot perceives the environment — whether it uses cameras to “see” the landmarks or uses laser beams to feel the environment — is another piece of the puzzle.

How Robots “See” a Room: Using Eyes vs. Using Lasers

To map a room, a robot must experience the space, and this is where its ‘eyes’ and ‘ears’ come in. There are basically two ways to do this, and they could not be farther apart.

Visual SLAM is the first and most obvious approach to this and simply uses a camera, such as a smartphone camera. Visual SLAM, like a person, scans the video feed for distinct, memorable characteristics (the sharp angle of a doorway; a rug’s unique design; a picture frame on a wall). Once these visual fingerprints have been identified, they can be used as landmarks to construct the robot’s map and determine its location. Essentially, the robot navigates based on what it sees and identifies locations from previous experiences.

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is another common method, but instead of relying on vision, it uses a form of ‘touch’. In this method, a sensor on the robot emits thousands of laser beams in a full circle and measures the distance to whatever they strike. Using data from the laser sensors, the robot constructs a highly detailed 3-D “dot-to-dot” representation of the environment. Unlike recognizing a picture of a chair, the robot recognizes the chair’s actual dimensions and placement.

In summary, both visual and lidar SLAM create different types of maps. Visual SLAM creates a map of identifiable features, whereas Lidar SLAM creates a map of specific geometric information. Ultimately, which sensor (visual or lidar) the robot uses depends solely on the task it must accomplish, the environment in which it will operate, and its cost.

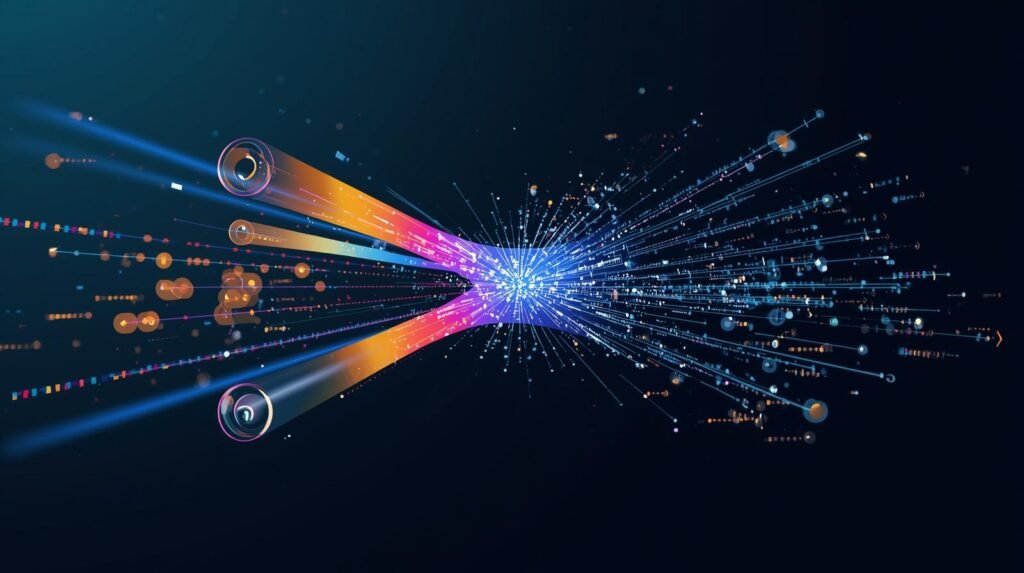

Sensor Fusion: Combining camera, LiDAR, and IMU data for accuracy

Sensor fusion combines data from multiple sensors to produce a clean, stable, and reliable estimate of motion and environment, which no single sensor could achieve independently. Sensor fusion is a major enabler of robust, functional simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) in real-world applications, rather than in lab-based environments where most of these systems have been developed.

The camera captures rich visual detail, such as texture, edges, and landmarks, enabling the robot to identify locations and track item positions over time. However, cameras are limited in their ability to perform well in low-light conditions, areas with motion blur, areas with glare, and featureless corridors. LiDAR provides a highly accurate representation of distance and geometric shape and can produce a high-quality three-dimensional model of the environment, even in complete darkness.

However, LiDAR is susceptible to noise near reflective surfaces and cannot detect thin objects. An inertial measurement unit (IMU) will measure the rate of change of acceleration and angular velocity at a high sampling rate and is therefore well-suited for tracking short-term motion; however, due to the lack of reference points, an IMU will begin to drift over time. Therefore, sensor fusion leverages each sensor’s strengths to compensate for the limitations of others.

Typically, in SLAM, sensor fusion begins by synchronizing and calibrating all sensors so they report measurements at the same location and time. During fast motion, the IMU can rapidly estimate the robot’s state between successive camera frames or LiDAR sweeps, thereby preventing loss of track. At the same time, LiDAR and camera observations will correct the robot’s position and orientation estimates to prevent the slow accumulation of error known as drift. The sensor fusion loop used in many SLAM algorithms—predict using the IMU and correct using either vision or LiDAR—has been shown to significantly improve accuracy and stability.

Sensor fusion combines multiple sensors to produce a coherent data stream. In indoor environments, sensor fusion from cameras & IMUs can be both lightweight and inexpensive; however, using LiDAR as a sensor can provide greater robustness in low-light conditions or repetitive hallway configurations.

When operating in outdoor environments, Sensor Fusion can be used to extend its capabilities with GPS (when GPS is available), while SLAM will continue to benefit from Sensor Fusion even when GPS is obstructed by buildings or tree canopy. Sensor Fusion improves on map consistency, provides reliable support for loop closure, and significantly reduces jitter that causes erratic robot movement.

In summary, Sensor Fusion is a sound foundation for developing dependable autonomous systems. It enables SLAM to remain accurate in near-real-time, to operate effectively when a sensor fails, and to produce maps and position information reliable enough for robots to use for navigation.

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Mapping the environment while tracking the robot’s position.

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) is a fundamental method for robots to build a map of unknown environments while determining their current location within them. Rather than using predefined maps, a robot will use sensor data to determine what it can currently see and where it must be positioned to perceive the environment.

The “localization” part of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping will answer the question, “where am I?” and the “mapping” part will provide an answer to the question, “what does the world look like?” The issue is that one of these problems relies heavily on the solution to the other: to localize yourself, you need a map, but you also need an accurate position estimate to place new map points.

To address this interdependence between localization and mapping, SLAM continually updates both simultaneously.

A basic example of how a Simultaneous Localization and Mapping loop may function is as follows: the robot predicts its motion (wheel odometry and IMU are common sources). Then the robot will compare the new sensor data from either a camera feature or a LiDAR point cloud with the previously collected sensor data. Once a comparison yields a good fit, the robot will adjust its estimated pose and update or add relevant map information. As this process is continually corrected over time, it will help reduce drift that would otherwise occur.

The need to operate in real time forces Simultaneous Localization and Mapping to rely on effective probabilistic methods. A number of SLAM applications use filter-based or graph-based optimization methods that support expressing uncertainty—meaning the robot does not track a single “best guess” but rather conveys how confident it is in each estimate. This is why many SLAM implementations may appear relatively stable even when some sensor readings contain noise.

The ability to include “loop closure,” i.e., the capability for the robot to recognize areas that have been previously visited, and then to adjust the map accordingly so as to prevent the slow deformation of the map, is another key component of good Simultaneous Localization and Mapping. Loop closure is critical for routes longer than typically considered short and is therefore a common metric for evaluating the effectiveness of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping implementations for practical deployment.

The choice of sensors significantly impacts the efficiency of a Simultaneous Localization and Mapping application. While cameras can provide rich visual information (i.e., they can detect a large number of unique features), they can be difficult to use in low-light environments.

In contrast, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensors measure distance to objects and can therefore be used to build a geometrically accurate representation of the environment. However, LiDAR sensors can sometimes become confused by transparent objects such as glass or by highly reflective surfaces. Therefore, many SLAM stacks use a combination of camera and LiDAR data to capture both the environment’s visual characteristics and its depth.

Practically speaking, teams will evaluate the effectiveness of a Simultaneous Localization and Mapping system based upon three primary criteria: accuracy, robustness, and usability of the generated maps for future navigation planning. When implemented successfully, Simultaneous Localization and Mapping enables robots to navigate warehouses, offices, and other outdoor environments with minimal initial configuration and to continue operating even as the physical structure of these environments changes over time.

Robot Navigation: How robots move and orient themselves in unknown environments

A critical aspect of Robot Navigation is the robot’s ability to move safely and purposefully, even without prior knowledge of the environment. Once the robot is in an area with no prior experience, Robot Navigation begins with perception. Perception for Robot Navigation involves the collection of sensory information from the robot’s various sensors, including cameras, LiDAR, sonar, and inertial sensors, to provide information about potential hazards, including walls, doors, people, drop-offs, etc.

The raw data collected by the robot’s sensors is typically noisy, so the robot must be able to interpret it quickly enough to take real-time action.

Another important component of Robot Navigation is the robot’s understanding of its own pose (its position and orientation). In cases where GPS is either unavailable or unreliable, a common approach used by many systems to determine the robot’s pose and build a map of the robot’s environment is SLAM (Simultaneous Localization And Mapping).

SLAM helps the robot distinguish between a new hallway and a familiar one; it also reduces drift when the robot relies solely on wheel odometry to estimate its pose. As the robot builds a more accurate map of its environment using SLAM, Robot Navigation can maintain consistency over longer distances and in more complex environments.

After the robot has obtained an estimate of the available free space, Robot Navigation moves into the planning phase. Planning in Robot Navigation involves two phases: global planning and local planning. Global planning determines the optimal route from the robot’s current location to the destination (e.g., a docking station), whereas local planning continually adjusts the path to avoid moving obstacles.

When selecting a route to follow, the robot will evaluate several different types of “costs” associated with each possible route, such as distance to the goal, the amount of space required between the robot and any hazards (i.e., safety margin), and the effort required for the robot to turn (i.e., turning cost). Based on the evaluation of these costs, the robot will select the most appropriate set of commands that align with its dynamics (i.e., how quickly it can accelerate, brake, and turn without slipping).

An additional benefit of SLAM is improved planning. Since the map built by the robot is more complete, the robot can better anticipate which paths will encounter tight areas or dead ends. This provides a better overall plan for the robot.

The last stage of control is to convert a planned path into motor commands. Robot Navigation uses controllers to compensate for all types of disturbances (uneven floor, bumps, etc.) and sensor delays in order to stay on the planned path. If the robot identifies it has strayed from the planned path, then the controller will either have the robot move back onto the path, or trigger replanning based upon the error detected.

If the environment changes, such as a door closing, the Robot Navigation system must be able to detect this change and make a decision to take a different path, rather than continuing to try to pass through the blockage. Robust Robot Navigation includes recovery actions. These include reversing away from an obstacle, pivoting to reorient the robot, and reducing speed to improve sensor tracking.

SLAM enables these recovery actions and provides a measure of confidence in the map’s accuracy. Therefore, if map confidence decreases during mission execution, the robot can slow down to collect more data before resuming navigation. In general, Robot Navigation distinguishes between a moving robot and a reliable moving robot, while SLAM provides the foundation for the robot’s motion to remain grounded in an accurate world model.

Robotics Navigation: Core technology enabling autonomous robot movement

Robotics Navigation is the core technology that enables a robot to navigate unfamiliar environments safely and efficiently to a destination point. To accomplish this, a robotics navigation system continuously answers three fundamental questions about its location and surroundings: 1) What is my current location? 2) What is surrounding me? 3) How do I reach my desired destination safely?

Robotics Navigation is essentially a single continuous loop in which Perception, Localization, Mapping, Planning, and Control are combined and operate in “real-time.” The first component of Robotics Navigation is Perception, which involves a robot sensing and collecting data from a variety of sensors, including cameras, LiDAR, Radar, Ultrasonic Sensors, Wheel Encoders, and Inertial Sensors.

The data collected is converted into useful signals representing Obstacles, Free Space, and Motion Estimates. Each sensor type has its own limitations (e.g., cameras struggle to see objects in low light, and LiDAR can be confused by reflective surfaces), and most robotic systems use multiple sensors to enable more robust, stable decision-making.

Localization is another critical component of Robotics Navigation. Localization is the process of determining the robot’s Pose (position and orientation). When GPS is either unavailable or unreliable (a common occurrence indoors), many robots rely on SLAM (Simultaneous Localization And Mapping) to determine the robot’s Pose by creating a map from sensor observations. A primary benefit of using SLAM is to limit the amount of drift caused by wheel slip and small measurement errors. Additionally, when the robot returns to an area it previously mapped, SLAM allows it to “re-anchor” itself, preventing loss of map accuracy.

There are several forms of SLAM, depending on the sensor(s) used and the application’s requirements (e.g., cost). The Outputs of the Mapping component of Robotics Navigation are used to maintain an up-to-date representation of passable areas, restricted areas, and structural elements (walls, shelves, etc.) within the environment. In addition, if a SLAM algorithm is used, the map created by the robot will continue to improve as the robot explores and environmental conditions change.

The next stage of robotics navigation is planning. Global planners plan the best route to get from one point to another; local planners respond to the changing world as they go – a person walking down the aisle, a cart coming out of nowhere, etc. This makes it easier for the robot to return to its original path when an obstacle appears on the map (e.g., a closed aisle) by enabling rapid replanning that does not require the robot to lose its position on the map via SLAM.

Robotics navigation also includes the control phase, where a planned path is converted into smooth steering and speed commands that are within the robot’s capabilities. Because SLAM provides continuous position updates to the robot, it can follow the path more accurately, stop at the correct location, and recover quickly and smoothly as uncertainty increases.

Real-Time Mapping: Maps updated instantly as robots move

Real-Time Mapping enables robots to obtain an updated view of the world with each movement, without relying on a preexisting map of the environment. Real-Time Mapping has applications in environments whose layout may change over time, such as when people walk through, doors open and close, pallets are left in aisles, or furniture is rearranged. To operate safely and efficiently in these changing layouts, the robot must have an up-to-date map of the area.

In Real-Time Mapping, the robot uses a continuous stream of sensor data (e.g., cameras, LiDAR, radar, wheel odometry, and IMUs) to build a real-time model of the surrounding environment’s free space and obstacles. Fast perception of surfaces and objects, along with the ability to quickly and accurately perform calculations that reflect the robot’s motion as it affects its point of view, are required for Real-Time Mapping. Outputs of Real-Time Mapping include 2D occupancy grids for indoor vehicle navigation, 3D point clouds for drone operation, and “semantic” maps that label regions (such as corridors, shelves, etc.) that contain different types of obstacles.

The accuracy of Real-Time Mapping depends on the robot’s ability to determine its position relative to the environment. While many systems utilize SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) to estimate the robot’s pose while simultaneously creating and correcting the map, the process of SLAM involves detecting and removing drift caused by minor errors in wheel slip or sensor noise, which occurs when the robot’s current observation is compared against previously observed features. When a high-quality SLAM pipeline is used, map updates are generated from the robot’s correct position, regardless of rapid turns or long routes.

When Real-Time Mapping detects a change, such as an obstacle, it immediately initiates a new plan to slow the robot, divert it around obstacles, or stop it. Real-Time Mapping also supports “loop closing.” When revisiting a previously mapped location, the mapping system will correct any warping of the original map that occurred during mapping. A good Real-Time Mapping system reduces the computational cost by compressing the collected data, limiting the number of frames used to create a map (keyframes), and/or reducing the detail of distant objects relative to nearby ones.

Real-Time Mapping ultimately allows for practical autonomous systems, enabling robots to operate effectively in dynamic environments, while maintaining adequate clearances, and allowing them to reach their goals safely and reliably. As SLAM confidence decreases, robots typically slow down and/or turn to collect better observations, since accurate localization is required to produce reliable Real-Time Maps. Therefore, SLAM is still tightly integrated into Real-Time Mapping in most modern robotic software stacks.

3D Mapping: Creating detailed 3D maps from robot sensor data

3D mapping is the method for creating high-resolution, three-dimensional models of environments from robot sensor data. The advantage of 3D mapping over a two-dimensional floor plan is the ability to capture height, shape, and depth. Drones, legged robots, warehouse vehicles, and inspection robots all need 3D mapping in order to move about and navigate uneven surfaces, including stairs, ramps, and shelves.

Typically, 3D mapping uses sensors such as LiDAR, depth cameras, stereo cameras, radar, and other sensors to create a “slice” of the world from the robot’s current position. For the slices of the world to become a single consistent model, the robot has to determine how it moved from one measurement to the next. This is typically where SLAM comes in: it tracks the robot’s motion, simultaneously building a more accurate map, and helps correlate new point clouds and depth images with previously created ones.

For many real-world applications, 3D mapping models space using a variety of methods, including point clouds, voxels, and meshes. Point clouds are easy to generate and ideal for obstacle detection. Voxel grids provide spatial information on occupancy (free vs. blocked) and are well-suited for occupancy maps. However, meshes tend to use less memory than voxels and are easier to visualize for inspection; however, they take longer to create and require additional computational resources.

As 3D mapping technology continues to evolve, memory usage will be addressed by downsampling data, retaining only keyframes, and/or dividing large areas of space into smaller sub-maps, which are then merged once complete.

Because robots do not have perfect sensors, accumulated errors from wheel slip, motion blur, and reflective-surface interference in sensor readings can distort measurements and misalign features, resulting in “ghosting” in the map. SLAM reduces these issues by matching features and structures across observations and loop closures as the robot returns to a previously visited location. When 3D mapping is performed reliably using SLAM, 3D maps remain sharp over longer distances and produce models that support both navigation and analysis.

In addition to supporting robotic navigation, 3D mapping enables a range of other high-level applications. For example, 3D mapping can help identify overhangs, narrow clearance paths, and traversable slope angles. In industrial inspections, 3D mapping can help identify structural deformations, missing components, and differences in inspection results between visits. For augmented reality (AR) and digital twin development, 3D mapping can provide the realistic spatial context necessary to create meaningful AR experiences and digital twin representations of physical environments.

Therefore, 3D mapping takes unprocessed sensor data and creates a measurable, navigable world model. Through SLAM, which provides consistent positioning and error correction, 3D mapping becomes accurate enough for autonomous operation rather than simply producing visualizations.

The “Aha!” Moment: How Robots Fix Their Mistakes

The robot uses dead reckoning to build the internal map of its surroundings. Dead reckoning works on a principle similar to how a human would travel a long distance in an unfamiliar environment, but instead of having a GPS to tell you exactly where you are, you are making an educated guess based on where you came from (the starting point) and which direction you were traveling when you made that guess.

Each time the robot uses dead reckoning to make a new guess about where it is in the world, there will be some error associated with that guess. The error may be very small, but if the robot continues to use dead reckoning for long enough, those errors can accumulate and distort its internal map of the world. If you imagine yourself walking through a dense forest, the farther you walk, the greater the chance that you will end up somewhere that doesn’t match the landscape you expected to see. Similarly, as the robot moves through its environment, it may begin to create duplicate representations of the same hallway or misalign the walls.

The robot gets back on track after its internal map of the world has drifted from reality by finding something it already knows. For example, let’s return to the earlier analogy of a robot finding its charging dock. When the robot finds the charging dock again, it immediately knows exactly where it is. That is because it is the only thing in the world that has been mapped and still exists today. Using that knowledge, the robot can then realign the remaining puzzle pieces relative to the charging dock. Once the charging dock is properly aligned in the robot’s internal map of the world, everything else falls into place, and the robot is once again accurately representing its surroundings.

Visual SLAM vs. LiDAR SLAM: Which is Better?

If we know that lasers work and cameras also work, then what will influence a manufacturer’s decision as to which one to use? The answer lies in the age-old trade-off in engineering: achieving performance versus paying less. In reality, there is no “better” way to accomplish a task, simply the better method to accomplish your given task.

The advantages of Visual SLAM include its low cost and compact size, since cameras are inexpensive and compact. Unfortunately, cameras suffer from the same limitations as the human eye. Cameras struggle in low-light conditions and when there are few or no distinct visual elements in an environment, such as a long, unbroken hallway. As a result, a robot that uses its vision to navigate a space without clearly defined landmarks is akin to traveling through a desert without any signposts.

LiDAR SLAM, on the other hand, is a high-accuracy system. LiDAR systems measure the distance between objects using laser beams and, therefore, are completely accurate in all lighting conditions (including complete darkness) and map their surroundings with precision. While accuracy comes at a cost (traditional LiDAR systems are larger and more expensive than a typical camera), they provide assurance and reliability for safe navigation in any environmental condition.

As noted above, the trade-offs between the two navigation methods depend on the products and applications currently available. A consumer robot vacuum is designed to be affordable, and therefore, a camera is an ideal solution to achieve this goal. On the other hand, a self-driving vehicle, where a failure to accurately map an area could have serious consequences, typically uses an expensive LiDAR system to ensure safe navigation under any environmental conditions. Regardless of whether the navigation system is based on a camera, LiDAR, or other sensors, each navigation system can make minor errors, which brings us to our final major question: how do robots correct these errors?

Where You Can Find SLAM Hiding in Plain Sight

The very same technology, SLAM, that enables you to correct your own mistakes is probably in your pocket right now. Have you ever looked into a smart home application to see how a new sofa would fit in your living room? Then you have experienced SLAM. The camera on your smartphone quickly creates a temporary visual map of your living room floor and walls, and uses computer vision to place a virtual object (the sofa) in the real space by generating a three-dimensional model that is both accurate and believable.

This fundamental concept of SLAM will be crucial for the future of transportation. Self-driving cars use GPS on open roadways, but once you enter a parking garage or tunnel, or narrow downtown streets, GPS loses its signal. In these areas, SLAM enables self-driving vehicles to create their own maps and safely navigate the environment. Autonomous robots will need to find ways to safely navigate spaces where they cannot call for assistance. One way to do this is to use SLAM.

SLAM technology also extends far beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. A rover on a distant planet, such as Mars, has no GPS system available to it. Therefore, rovers such as NASA’s Perseverance Rover must rely solely on SLAM to autonomously traverse Martian terrain. The rover creates its own map of the terrain, including craters and rock fields, and thus its own guidebook to the alien terrain no human has walked on. Each mile the rover travels is a testament to the capabilities of SLAM technology.

Whether you are in your living room, on Mars, or anywhere in between, SLAM technology enables machines to move and explore. It is a universal answer to machine spatial awareness.

So, How Does a Robot Really Know Its Location?

What was once thought to be magical is now shown to simply be a methodical, sequential approach to solving the “lost in the dark” dilemma. In addition to receiving a fully accurate map of its surroundings, a robot using SLAM will create its own map and develop an understanding of its position relative to its surroundings during each exploration. It basically learns the layout of a new space by developing its own map.

SLAM creates a map of a new environment by decomposing an almost impossible task into smaller ones. As a person attempts to create a map of a shopping mall, they are also attempting to locate their own position on the map (the “You Are Here” icon). The real power behind the self-localization capabilities of robots comes from those “aha” moments when a robot identifies a familiar landmark; this moment causes the entire mental image of the robot’s environment to become clear and corrects any previous inaccuracies in the robot’s perception of its surroundings.

When you see a robot vacuum cleaning up a room with precision, or hear about a rover that is exploring Mars, you will see them as examples of the continuous, deliberate cycle of a robot perceiving its surroundings, then moving, and then updating the map of its surroundings. This ability to perceive and create awareness of space enables a device to move beyond being a mechanical device and work autonomously as a partner in the future of robotics, one mapped room at a time.

Conclusion

SLAM transforms a robot from a machine that merely operates into a machine that can operate with intent within the real world. A robot can build and refine a map while determining its location and how to navigate new areas, adapt to layout changes, and continue operating even without GPS access. The top SLAM applications are built around combining high-quality sensors (cameras, LiDAR, and IMUs) along with sensor fusion and probabilistic methods to manage uncertainty rather than ignore it.

Rather than a single “miracle” application, SLAM is a collection of techniques tailored to a given environment and cost constraints: lightweight SLAM using vision, LiDAR-based SLAM for precise geometric data, and hybrid techniques that combine these approaches. Real-time mapping and loop-closing capabilities enable consistent map maintenance across long routes, improving navigation, planning, and safety.

As computing resources increase and sensing capabilities improve, SLAM becomes more reliable, more affordable, and more widespread. SLAM is a foundational component of autonomous operation, whether in warehouse automation, hospital use, package-delivery robots, unmanned aerial vehicles, or household appliances.

FAQs

- What does SLAM stand for, and why is it important in robotics?

SLAM means simultaneous localization and mapping. It enables a robot to determine its location and create a map of an area without prior knowledge of its layout; both are required for autonomous navigation, especially in environments such as offices or buildings where GPS performance is poor. - How do robots perform SLAM without GPS?

A robot uses data from its onboard sensors (cameras, LiDAR, wheel encoders, and/or IMU) to determine how far it has traveled and to detect what it can identify as “landmarks.” Measurements of motion and landmark detections from the robot’s onboard sensors are fused in real time using SLAM algorithms, enabling the algorithm to estimate the robot’s position and update the map. - What’s the difference between mapping and localization in SLAM?

The map represents the environment (walls, obstacles, landmarks, etc.). The robot’s current position and orientation within this map are determined by the localization component of SLAM. Therefore, SLAM is solving both problems simultaneously. - What is loop closure, and why does it matter?

When a robot returns to a location it has previously visited, it recognizes that it has closed a loop. Loop closures enable SLAM to correct accumulated drift (the gradual accumulation of error over time) in its maps, improving consistency and long-term navigation accuracy. - What sensors are commonly used for SLAM, and which is best?

The most common sensors used for SLAM are cameras (for visual SLAM), LiDAR (for geometry-focused SLAM), and IMU (for motion tracking). What is best depends on the specific use case. Cameras provide detailed representations but are relatively inexpensive. LiDAR provides more robust and accurate results in lower lighting conditions but is more expensive than cameras. Most commercial SLAM systems use both to increase overall reliability.